Copyright is an intangible right given to the author of an original artistic work. It protects the work from reproduction or publishing for monetary gain without the consent of the owner. The words generally used while discussing infringement are reproduction, translation, adaptation, derivation and transformation. Though it may seem that they have same or similar meaning, in the theory of copyright, they have a different status.

In the case of a literary work, copyright means the exclusive right:

- To reproduce the work

- To issue copies of the work to the public

- To perform the work in public

- To communicate the work to the public.

- To make cinematograph film or sound recording in respect of the work

- To make any translation of the work

- To make any adaptation of the work.

Therefore, a movie adaptation of a book cannot be made without the consent of the author. Similarly, translation also infringes copyright as they are essentially a reproduction of someone’s original work for monetary reasons. Raising eyebrows, this has given heat to the recent discussions as to whether an existing work when translated into Braille will account to a copyright infringement or not?

CAN BRAILLE INFRINGE COPYRIGHT?

The questions which prompt in mind are:

- What is Braille-translation or transliteration?

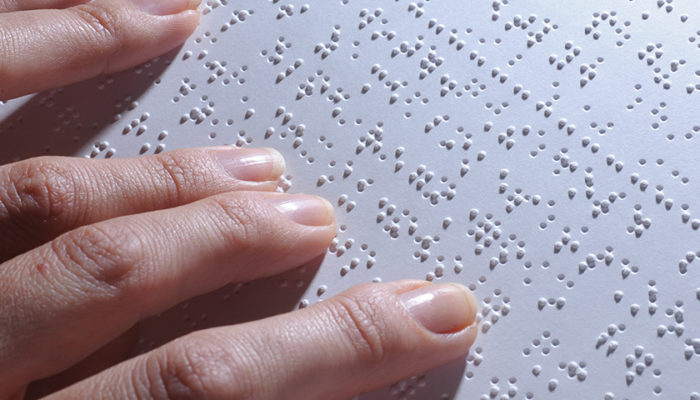

Braille is a palpable reading and writing system used by blind and visually impaired people. Represented by the patterns of raised dots that one can feel with their fingertips, it enables the visually impaired to study, regardless of the language and is hence acting as a universal code for all the languages.

Translation implies the conversion from the original language to a different alternate language. Since Braille is not a language, the term translation cannot be used in this context. Taking an example, if we convert “Bhagwan”( in Hindi) to Braille, the output cannot be regarded a translation as it remains in Hindi and does not feature conversation into any other language such as English. Therefore, such conversion is not considered as a translation and is instead termed as a transliteration. This way, Braille does not violate section 14(a)(v) of the copyright act, 1957 and hence such conversion shall not attract infringement charges.

- Does conversion of literary work into Braille come under the scope of adaptation and reproduction?

Adaptation involves the preparation of a new work in the same or different form, based upon an already existing work involving re-arrangement or alteration of the same. If literary work is converted into Braille, it will lead to the violation of rights under section 14(a)(vi).

Will conversion of literary work into Braille lead to reproduction of work under section 14(a)(i)?

Interpretation of ‘reproduction of work’ is debatable and the conversion of literary work into the six-dot Braille code will solely, and exclusively depend upon this interpretation. Braille is technically sticking to the contents, but for expression to be categorized as reproduction, conversion may remain true to content or expression or both. The new cause (zb) added to section 52(1) of the copyright act, 2013 provides for fair use of the work for the benefit of the disabled; facilitates adaptation, reproduction, issue of copies or communication to the public of any work in an accessible format.

Since Braille is a part of accessible format, section 52(1)(zb) suggests that the expression “adaptation, reproduction and communication to the public” can be used with respect to it hence, generating the clarity on Braille fitting into the scope of adaptation and reproduction.

Whether Braille can cause copyright infringement?

The district court in Authors’ Guild v. Hathitrust, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22370, (S.D.N.Y. 2013), had held that the digitization of millions of books made available to people with disabilities was a transformative use, even though each of the books’ contents was reproduced in their entirety and without any content modification. Should the court of appeals affirm this holding, the court would be indicating that there need not be any kind of expressive transformation in the copyrighted works and the mere putting of the copyrighted works to a different purpose from that which the copyright owners intended shall be considered.

In Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539, (1985), the Supreme Court held that the act of the news magazine, The Nation, “scooping” portions of President Gerald Ford’s unpublished memoirs, just weeks before its authorized publication in a rival magazine amounted to copyright infringement. The court held that the fair use defense did not apply to The Nation’s actions. The court noted that “[every] commercial use of copyrighted material is presumptively an unfair exploitation of the monopoly privilege that belongs to the owner of the copyright.” Furthermore, the court explained that “[t]he crux of the profit/nonprofit distinction is not whether the sole motive of the use is monetary gain but whether the user stands to profit from exploitation of the copyrighted material without paying the customary price.”

Analyzing the above judgments, we may conclude that the conversion of literary work into Braille will be covered under copyright infringement if the proper license is not taken.